Last Sail

It was a cold and dreary afternoon in late November when I took Stephen Warrick out for the fourth time, with his pal Lisa Fronkenberger. They took ASA 101 together with two other people whom they will join for a combined 103/104 that will take them three days and two

York County tourism officials do a masterful job attracting tall ships from all over the world to Yorktown. One recent arrival was also the biggest, El Galleon. It’s a replica that epitomizes large 17th century ships that were used for trade, spreading Spain’s influence abroad. She weighed 500 tons and extended 164 feet long and 33 feet wide. Three masts furl seven sails comprising nearly 10,000 square feet. The ship has covered 35,000 miles by visiting ports in four of the five world continents as an elegant ambassador for Spain.

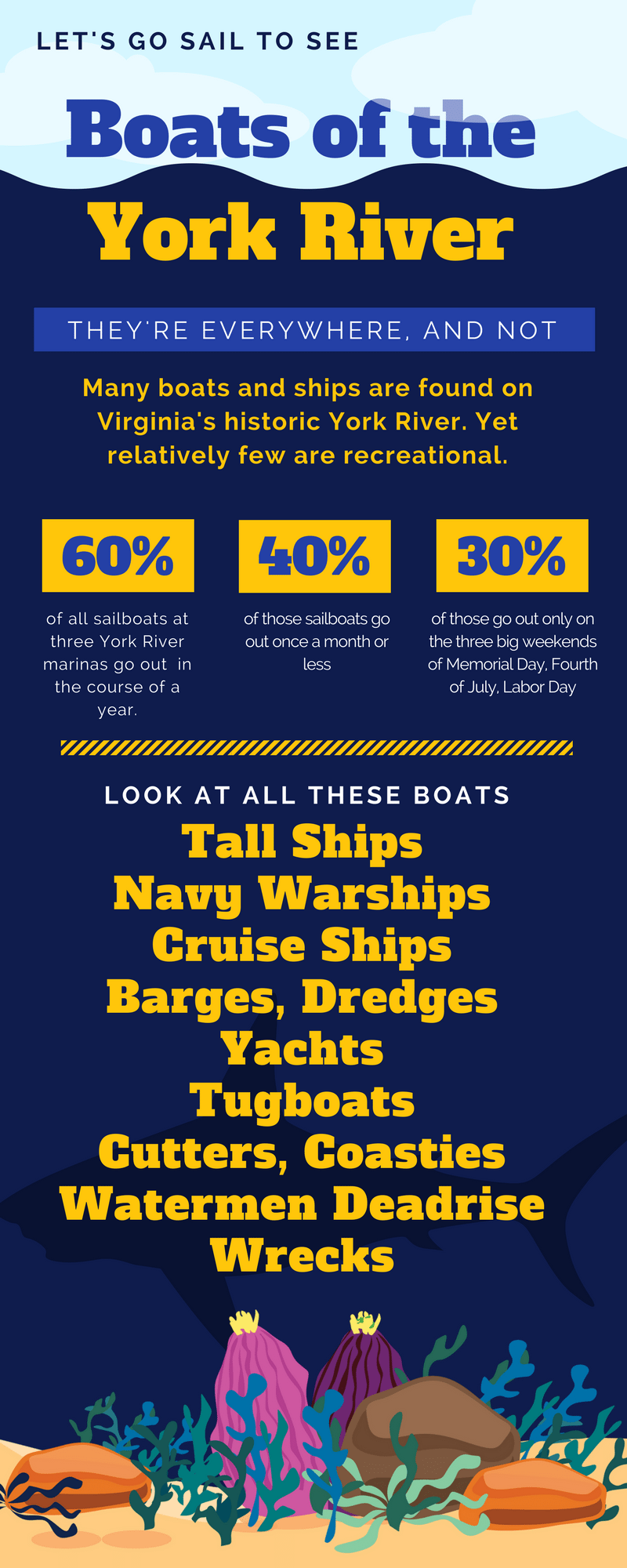

York County tourism officials do a masterful job attracting tall ships from all over the world to Yorktown. One recent arrival was also the biggest, El Galleon. It’s a replica that epitomizes large 17th century ships that were used for trade, spreading Spain’s influence abroad. She weighed 500 tons and extended 164 feet long and 33 feet wide. Three masts furl seven sails comprising nearly 10,000 square feet. The ship has covered 35,000 miles by visiting ports in four of the five world continents as an elegant ambassador for Spain. Next in terms of size, nearly every week one or two US Navy warships glide up from the Norfolk fleet to re-arm at Yorktown Naval Weapons Station. The Coleman Bridge swings open for only one client, the Navy. An amazing distinction is that these ships throw no visible wake. But ten minutes after they pass, you can see a faint outline of the wake and hear it wash onto shore a few minutes later. Historians say the breakthrough at Midway in World War II was that we spotted the Japanese wakes before we saw the ships. Today, the accompanying tugboats throw a bigger wake. In 2019 more Navy traffic was apparent as the Trump adminstration rattled sabers over the Middle East.

Next in terms of size, nearly every week one or two US Navy warships glide up from the Norfolk fleet to re-arm at Yorktown Naval Weapons Station. The Coleman Bridge swings open for only one client, the Navy. An amazing distinction is that these ships throw no visible wake. But ten minutes after they pass, you can see a faint outline of the wake and hear it wash onto shore a few minutes later. Historians say the breakthrough at Midway in World War II was that we spotted the Japanese wakes before we saw the ships. Today, the accompanying tugboats throw a bigger wake. In 2019 more Navy traffic was apparent as the Trump adminstration rattled sabers over the Middle East. Oil barges anchor in the middle of the York River, just north of channel marker R-22. Some of them carry 400,000 gallons to offload at the Yorktown Terminal, for piping to Philadelphia. Others lie empty, waiting to be filled with oil for water transit to—Philadelphia. (The business plan makes no sense.) Nearby the dock, dredges spent an entire year in 2017 digging the river bottom lower for an electrical line. They pulled up muck to be dropped into scows and dumped at designated “spoils” spots in the Chesapeake Bay.

Oil barges anchor in the middle of the York River, just north of channel marker R-22. Some of them carry 400,000 gallons to offload at the Yorktown Terminal, for piping to Philadelphia. Others lie empty, waiting to be filled with oil for water transit to—Philadelphia. (The business plan makes no sense.) Nearby the dock, dredges spent an entire year in 2017 digging the river bottom lower for an electrical line. They pulled up muck to be dropped into scows and dumped at designated “spoils” spots in the Chesapeake Bay.

The big red tugs by Moran of New York City precede the Navy warships under the bridge to catch them and guide them into the NWS pier. The wake of the tugs is greater than that of the destroyers and cruisers that tower over them. Mariners are wise to hail tugs as they proceed so as to convey your intentions and avoid their path. Smaller tugs accompany anchored oil barges to prevent any runaways. They tow the barges at sea and then reorganize to push them along in the Bay and the river. Tiny tugs push small barges for pile driving. All tugs hail on Channels 16 and 13, and they like you to catch their name the first time as a matter of respect.

The big red tugs by Moran of New York City precede the Navy warships under the bridge to catch them and guide them into the NWS pier. The wake of the tugs is greater than that of the destroyers and cruisers that tower over them. Mariners are wise to hail tugs as they proceed so as to convey your intentions and avoid their path. Smaller tugs accompany anchored oil barges to prevent any runaways. They tow the barges at sea and then reorganize to push them along in the Bay and the river. Tiny tugs push small barges for pile driving. All tugs hail on Channels 16 and 13, and they like you to catch their name the first time as a matter of respect. These long, low boats are often hand-made and are used to catch crab and oysters. You can tell the difference between the boats because the oyster deadrise has a framework to hold the dredging scoop (photo, right). Crab boats stay close to shore in 10-15 feet of water. Their crab pots are useful guides to checking for low water and shoals. Avoid them at all costs so the lines don’t foul your keel, rudder or prop and so that you don’t run aground.

These long, low boats are often hand-made and are used to catch crab and oysters. You can tell the difference between the boats because the oyster deadrise has a framework to hold the dredging scoop (photo, right). Crab boats stay close to shore in 10-15 feet of water. Their crab pots are useful guides to checking for low water and shoals. Avoid them at all costs so the lines don’t foul your keel, rudder or prop and so that you don’t run aground. Sailboats stand at the top of the recreational pyramid for elegance, rules of the road, and skill required to operate. Motorboats abound too, but sometimes they run aground on the shoal of the entrance to Sarah Creek. Scrutinize the York River chart before getting underway. The owner typically sets the auto-pilot for a course and then goes below for a cup of coffee. Among other ships of the York, this is pretty pathetic.

Sailboats stand at the top of the recreational pyramid for elegance, rules of the road, and skill required to operate. Motorboats abound too, but sometimes they run aground on the shoal of the entrance to Sarah Creek. Scrutinize the York River chart before getting underway. The owner typically sets the auto-pilot for a course and then goes below for a cup of coffee. Among other ships of the York, this is pretty pathetic.