People sometimes ask, “Is there a faster way to sail?” Oh yes, on ice! Before global warming, people used to sail on ice. It’s long forgotten, but our kin from the 1800s convey that ice sailing has a storied past.

Americans live for speed and always have. Beginning with horse racing in 17th century New York and later Virginia, it has been part of our culture of adventure to go fast and win. Speed underlies our heritage as well. A century after the colonies declared independence, people began moving inland with dispatch. During the Oklahoma land rush of 1889 families roared from a starting point out into the prairie to claim their 160 acres.

Until the railroad came along, riding a horse was as fast as travel got. But in certain northern climates, hardy sportsmen with time on their hands had an idea. They developed an ingenious jury-rigged sailboat on a sled that could reach speeds of 50 mph. As early as 1790, a primitive square box on three runners was skidding serenely along the frozen Hudson River, north of New York City.

Just a few years earlier, the lower river valley was “the central and critical ground of the whole momentous struggle” of the American Revolution, according to historian Francis Whiting Halsey in a 1907 lecture. Control of the river was pivotal in the battles of Harlem Heights, Princeton and Trenton. It was also here, at West Point, where Benedict Arnold betrayed his country.

Ice Sailing by the Dutch

The Dutch began ice boating in the 1600s, though hardly for the sport of it. By attaching skates to a board and the board to his boat, a merchant could take a shortcut to transit the frozen canals of Amsterdam and transport his goods to market. There isn’t much scholarship on the matter for it was simple expediency. “It is hard to say just when the first ice-boat was built,” is about as definitive as the origin was explained in a 1913 text, which turned fanciful: “Probably a small boy with his coat spread out before the wind furnished the idea.”

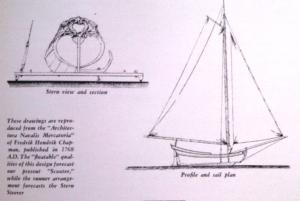

An engraving of a Dutch iceboat from 1605 is thought to be the earliest visual record of the vessel, if you can call it that. Sailboats retrofitted with runners could navigate the frozen canals and bays near the North Sea. An engraving from 1768 shows a conventional Dutch sailing sloop with a big cross plank running under the hull and a steel skate blade on each side. A how-to text from 1962 picks up the story.

This was surely the ancestor of all stern-steerers. Moreover, this early Dutch craft could be sailed both in winter and summer. By removing the cross plank and plugging the attachment bolt holes, the seaworthy hull could be returned to sailing duty on the water. The practical Dutch continued to build this type of convertible ice boat for many years, and just prior to World War II almost identical versions still were “sleigh-sailing” in Holland.

Dutch Started Ice Sailing

It was the Dutch who settled along the Hudson River, and they brought their enterprise with them.

There appeared in 1768 the oldest extant set of plans for an ice boat. Chapman’s Architectura Navalis Mercatoria shows a veritable ice yacht as a Dutch sloop with a cross plank forward of the hull and runners on each side. Come summer, the rails were removed to restore the boat to water sailing.

Large boats built of sturdy timber could transport lumber across rivers and lakes, reducing roundabout travel over land. The commercial concept extended to Lake Erie and Lake Michigan, where eventually ice sailing became popularized for recreation. The boat Zero was built in 1938 and sails to this day.

Ice sailing would have been possible as far south as Philadelphia in the winter of 1777-78 because for three months temperatures hovered from 6 to 16 degrees and froze the rivers solid. That winter was made famous by the Battle of Valley Forge, where American troops had better things to do than ice sail, coping with heavy snowfalls as well as the cold in their surprise attack on the British.

A hundred years later, ice yachts raced railroad trains down the coastline of the Hudson Valley. The boats were based in Poughkeepsie, near the Roosevelt compound at Hyde Park. In 1869, FDR’s Uncle John built a 69-foot behemoth called Icicle, which flew 1,070 feet of canvas sail and weighed more than a ton. It took a flatbed rail car to transport Commodore Roosevelt’s Icicle to races in the Midwest on Lake Michigan. Rare film footage was shown briefly on the recent Ken Burns documentary about Theodore, Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt.

The commodore established the Hudson River Yacht Club for sailing on soft water and hard. He gave his nephew Franklin an iceboat that has since been preserved. Hyde Park lies six miles north of Pocantico Hills, the Rockefeller estate famously described as “the spiritual center of the family’s existence.”

A smaller version of the Icicle was clocked at more than 100 mph, which is astonishing considering a horse could do 25 and a train 50 while the automobile and airplane were yet to be invented. By then, in 1908, the Clarel reached 140 mph on the Shrewsbury River in New Jersey. These days, expert snow skiers like to get close to the tree line on the slopes to gain a greater sensation of speed. Back then, performance iceboats raced trains – and beat them. A more typical iceboat raced 20 to 30 mph, which made the ride harrowing as the sailor sat only a few inches from the surface zooming underneath. Motorcyclists can relate. The idea of wearing helmets never occurred to the ice-boaters, since they hadn’t been invented yet for sports.

Ice sailing would be nearly forgotten now except for the winter of 2013-14, among the coldest on record in the Midwest and Northeast where the sport flourishes sporadically. Sustained temperatures below freezing thickened the ice on rivers and lakes to the 4-12 inches required to withstand the pressures of everyone scurrying about. Ice sailing was likely active on Lake Michigan in 1903-04 because Chicago’s average temperature for the entire winter was 18 degrees. Baltimore averaged 5 degrees throughout March 1873, freezing the Patapsco River to a thickness unimaginable today. Virginia’s rivers occasionally froze over during the 20th century, but not to the thickness required for ice sailing.

The speed of the craft derives from a near frictionless set of rails scooting over the ice, similar to how huge catamarans rose up on carbon fiber hydrofoils in the 2013 America’s Cup race of 70-foot mega-yachts. Those boats hit 55 mph, which is only half of what a modern ice sailboat can do.

Racing dates from 1861 with the formation of the Poughkeepsie Ice Yacht Club. The iceboats steered from the stern, much like a conventional sailboat. But they had a tendency to spin out dangerously in what were quaintly termed “flickers.” A typical race would run a triangle of one mile each side to test the sailor’s skills reaching upwind and heading downwind.

A how-to book from 1938 differentiates sailing on ice from water. To get going on ice, one has to push the boat by foot and jump on, like a modern bobsled. The author quoted a winner of many ice races: “Well, in light breeze you sail ’er something like a boat, but when it breezes up you driver ’er like an automobile!”

The box on skates gave way to a muscular rig that was lighter and stronger while still large. The frame was nothing more than a single-piece backbone with a crossbow at a right angle, a veritable kite. The seating area resembled a large snowshoe.

In a good year, the season lasts two weeks to a month in the Northeast. It runs longer in the upper Midwest, but not until after Jan. 1 when the ice is good and thick. With the onset of global warming, five years can elapse between sailable seasons because it’s too warm. The winter of 2012-13 provided only four hours of sailing on the Hudson.

Modern racers are sleek and lightweight wishbows that steer at the bow for greater stability, such as it is. Fleets break into four classes by size, and the one-man version resembles sailboarding on water. It derives from an earlier craft.

The migration west of ice sailing traces a timeline researched by the Grand Traverse Yacht Club. Yachtsmen from Wisconsin visited the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, where they copied a Poughkeepsie design and eventually churned out 85 boats for racing off the coast of Madison on Lake Michigan.

At New Hamburg on the Hudson River, Archibald Rogers formed the Ice Yacht Challenge Pennant of America. He sailed his Jack Frost rig against Roosevelt’s Icicle. Other iceboat yacht clubs popped up on the Navesink River in New Jersey, Gull Lake near Kalamazoo, Lake Ontario at Kingston, Lake Michigan at Oshkosh, and the length of Lake Champlain in Vermont.

The races enjoyed commercial sponsorship as early as 1896 with the distiller Hiram Walker & Sons. Newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst deeded a trophy for races with boats flying 450 square feet of sail. That’s equivalent to the mainsail of a modern 30-foot sailboat.

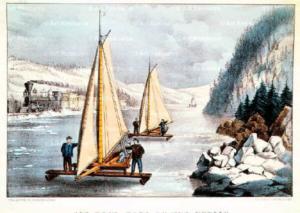

Ice sailing proved perfect for Currier and Ives, who lived in New York during the 1880s. Their print of “Ice Sailing on the Hudson” remains iconic. There is precious little contemporary literature on ice boating since it was a narrow field with relatively few participants. Iceboating (1913) was a text outlining the copious specs of various boats. It also identified the best venues in America’s colder climes. Congress got into the spirit by issuing a brief report in 1913, Ice-Boats for the Potomac River. But it had to do with ice-breaker boats instead. Hungary went so far as to issue a commemorative stamp.

During the Great Depression, the Detroit News embarked on a unique promotion whose success set a record for longevity. Many people couldn’t afford much in the way of travel or recreation. So the newspaper held a contest to design a small iceboat racer that readers could build on their own. The winner was 12 feet long and 2 feet wide. Today the International DN-class is the most popular iceboat in North America and Europe. It can sustain 55 mph.

The North Shrewsbury Ice Boat and Yacht Club of New Jersey spent ten years restoring the 50-foot iceboat Rocket, circa 1929. The name proved apt, as it soared to 57 mph in brisk winds. Rocket is among several restored ice sailors in the accompanying You Tube video.

Today’s ice sailors watch more than the temperature. They look for rains that glaze the ice overnight. Then they rush overland by car to get there early in the morning, with their rigs lashed on the roof. Surface thaws from sunlight can smooth out the surface for overnight chilling. Brisk winds can play havoc as the ice sets up. The surface takes on a ripple effect that is bumpy — and deadly. Sailors liken it to riding a roller coaster. At high speeds, the boat can go airborne and flip. The result resembles an F1 hydroplane speedboat when it flips at 200 mph. It’s the amateur’s version of extreme sailing by hydroplaning catamarans.

“Land sailors” are a less elegant racer and setting. Glorified go-karts on three wheels traverse long stretches of smooth salt flats at Bonneville Speedway in Utah. Drivers wear seatbelts and helmets in case they tip as they reach 70 mph. The dry lakes of southern California offer similar wide-open wind and space, compounded by swirls of blinding dust. At least one freezes in the event.

Let’s Go Sail

Scroll down Rates and pick a day for a sailboat charter. Scroll down Reviews on Trip Advisor. Go back to the Home Page of Williamsburg Charter Sails.

ice sailing has storied past ice sailing has storied past ice sailing has storied past ice sailing has storied past ice sailing has storied past ice sailing has storied past