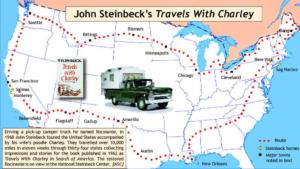

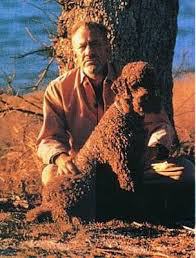

When he published “Travels with Charley” in 1962, John Steinbeck was arguably the most famous living author in America. His bestsellers traced American society during the mid-century in “The Grapes of Wrath,” “Cannery Row” and “East of Eden,” among other books.

Before he set out to see the country, Steinbeck had to prepare his boat for Hurricane Donna as it bore down on the eastern end of Long Island in 1960. It was one of the worst hurricanes of the 20th century. Every sailor and boater who’s been through a hurricane can appreciate his detailed prep for the mooring and the frustrating aftermath.

Before he set out to see the country, Steinbeck had to prepare his boat for Hurricane Donna as it bore down on the eastern end of Long Island in 1960. It was one of the worst hurricanes of the 20th century. Every sailor and boater who’s been through a hurricane can appreciate his detailed prep for the mooring and the frustrating aftermath.

I have a twenty-two-foot cabin boat, the Fayre Eleyne. I battened her down and took her to the middle of the bay, put down a huge old-fashioned hook anchor and half-inch chain, and moored her with a long swing. With that rig she could ride a hundred-and-fifty mile wind unless her bow pulled out.

Donna sneaked on. By early morning we knew by radio that we were going to get it, and by ten o’clock we heard that the eye would pass over us and that it would reach us at 1:07—some exact time like that. Our bay was quiet, without a ripple, but the water was still dark and the Faye Eleyne rode daintily slack against her mooring.

Our bay is better protected than most, so that many small craft come cruising in for mooring. And I saw with fear that many of their owners didn’t know how to moor. Finally two boat, pretty things, came in, one towing the other. A light anchor went down and they were left, the bow of one tethered to the stern of the other and both within the swing of the Fayre Eleyne. I took a megaphone to the end of my pier and tried to protest against this foolishness, but the owners either did not hear or did not know or did not care.

Our bay is better protected than most, so that many small craft come cruising in for mooring. And I saw with fear that many of their owners didn’t know how to moor. Finally two boat, pretty things, came in, one towing the other. A light anchor went down and they were left, the bow of one tethered to the stern of the other and both within the swing of the Fayre Eleyne. I took a megaphone to the end of my pier and tried to protest against this foolishness, but the owners either did not hear or did not know or did not care.

The wind struck on the moment we were told it would, and ripped the water like a black sheet. It hammered like a fist. The whole top of an oak tree crashed down, grazing the cottage where we watched. The next gust stove on of the big windows in. I forced it back and drove wedges in top and bottom with a hand ax. Electric power and telephone went out with the first blast, as we knew they must. An eight-foot tide was predicted. We watched the wind rip at earth and sea like a surging pack of terriers. A boat broke loose and tobogganed up on the shore, and then another. Houses build in the benign spring and early summer took waves in their second-story windows. The Faye Eleyne rode gallantly, swinging like a weather vane away from the changing wind.

The wind struck on the moment we were told it would, and ripped the water like a black sheet. It hammered like a fist. The whole top of an oak tree crashed down, grazing the cottage where we watched. The next gust stove on of the big windows in. I forced it back and drove wedges in top and bottom with a hand ax. Electric power and telephone went out with the first blast, as we knew they must. An eight-foot tide was predicted. We watched the wind rip at earth and sea like a surging pack of terriers. A boat broke loose and tobogganed up on the shore, and then another. Houses build in the benign spring and early summer took waves in their second-story windows. The Faye Eleyne rode gallantly, swinging like a weather vane away from the changing wind.

The boats which had been tethered one to the other had fouled up by now, the tow line under propeller and rudder and the two hulls bashing and scraping together. Another craft had dragged its anchor and gone ashore on a mud bank.

The boats which had been tethered one to the other had fouled up by now, the tow line under propeller and rudder and the two hulls bashing and scraping together. Another craft had dragged its anchor and gone ashore on a mud bank.

The wind stopped as suddenly as it had begun, and the tide rose higher and higher. The radio told us we were in the eye of Donna, the still and frightening calm in the middle of the revolving storm. And then the other side struck us, the wind from the opposite direction. The Fayre Eleyne swung sweetly around and put her bow into the wind. But the two lashed boats dragged anchor, swarmed down on Fayre Eleyne, and bracketed her. She was dragged fighting and protesting downwind and forced against a neighboring pier, and we could hear her hull crying against the oaken piles. The wind registered over ninety-five miles now.

I found myself running, fighting the wind around the head of the bay toward the pier where the boats were breaking up. I think my wife, for whom the Fayre Eleyne is named, ran after me, shouting orders for me to stop. The floor of the pier was four feet under water, but piles stuck and offered hand-holds. I worked my way out little by little up to my breast pockets, the shore-driven wind spalling water in my mouth. My boat cried and whined against the piles, and plunged like a frightened calf. Then I jumped and fumbled my way aboard her. For the first time in my life I had a knife when I needed it. The bracketing wayward boats were pushing Eleyne against the pier. I cut anchor line and tow line and kicked them free, and they blew ashore on the mudbank. But Eleyne’s anchor chain was intact, and that great old mud hook was still down, a hundred pounds of iron with spear-shaped flukes wide as a shovel.

I found myself running, fighting the wind around the head of the bay toward the pier where the boats were breaking up. I think my wife, for whom the Fayre Eleyne is named, ran after me, shouting orders for me to stop. The floor of the pier was four feet under water, but piles stuck and offered hand-holds. I worked my way out little by little up to my breast pockets, the shore-driven wind spalling water in my mouth. My boat cried and whined against the piles, and plunged like a frightened calf. Then I jumped and fumbled my way aboard her. For the first time in my life I had a knife when I needed it. The bracketing wayward boats were pushing Eleyne against the pier. I cut anchor line and tow line and kicked them free, and they blew ashore on the mudbank. But Eleyne’s anchor chain was intact, and that great old mud hook was still down, a hundred pounds of iron with spear-shaped flukes wide as a shovel.

Eleyne’s engine is not always obedient, but this day it started at a touch. I hung on, standing on the deck, reaching inboard for wheel and throttle and clutch with my left hand. And that boat tried to help—I suppose she was that scared. I edged her out and worked up the anchor chain with my right hand. Under ordinary conditions I can barely pull that anchor with both hands in a calm. But everything went right this time. I edge over the hook and it tipped up and freed its spades. Then I lifted it clear of the bottom and hosed into the wind and gave it throttle and we headed into the goddamn wind and gained on it. A hundred yards offshore I let the hook go and it plugged down and grabbed bottom. The Faye Eleyne straightened and raised her bow and seemed to sigh with relief.

The best way to read “Travels with Charley” is to listen to it on audio disc under the narration of Gary Sinise. It may seem incongruant that a famous actor would stoop to reading a book aloud, but Sinise reveres Steinbeck. Sinise performed in the 1988 stage version of “The Grapes of Wrath.” He also directed and starred in the 1992 film version of “Of Mice and Men.”

The best way to read “Travels with Charley” is to listen to it on audio disc under the narration of Gary Sinise. It may seem incongruant that a famous actor would stoop to reading a book aloud, but Sinise reveres Steinbeck. Sinise performed in the 1988 stage version of “The Grapes of Wrath.” He also directed and starred in the 1992 film version of “Of Mice and Men.”