Underwater archeology is an important field that is poorly funded, according to John D. Broadwater, a world-renowned practioner who’s now pursuing his 11th ship under the York River. Broadwater once explored the Titanic and helped raise booster rockets from the Apollo space flights. His career has spanned 50 years, with much of it right here in the York River.

He spoke Feb. 8 to a packed house of 250 at the Williamsburg Regional Library about the lost ships from the 1781 Siege of Yorktown. His newest role is chief archaeologist and vice president of JRS Explorations in Yorktown, a private venture.

He spoke Feb. 8 to a packed house of 250 at the Williamsburg Regional Library about the lost ships from the 1781 Siege of Yorktown. His newest role is chief archaeologist and vice president of JRS Explorations in Yorktown, a private venture.

Broadwater was instrumental during the 1980s in finding and painstakingly researching and preserving the only intact ship from 1781. It’s among 37 positively identified and there may be more. Today, “I keep going back, because the Yorktown ships are in my blood,” he said. This despite the fact the water is so opaque “that sometimes I can’t see my fingers in front of me. No cameras, it’s all by feel of the hands.”

“Lord Cornwallis chose Yorktown as a place that could be defended. The river is one of the deepest in America in terms of natural dredging. He planned to wage a naval campaign in the Chesapeake Bay the next spring.”

“Lord Cornwallis chose Yorktown as a place that could be defended. The river is one of the deepest in America in terms of natural dredging. He planned to wage a naval campaign in the Chesapeake Bay the next spring.”

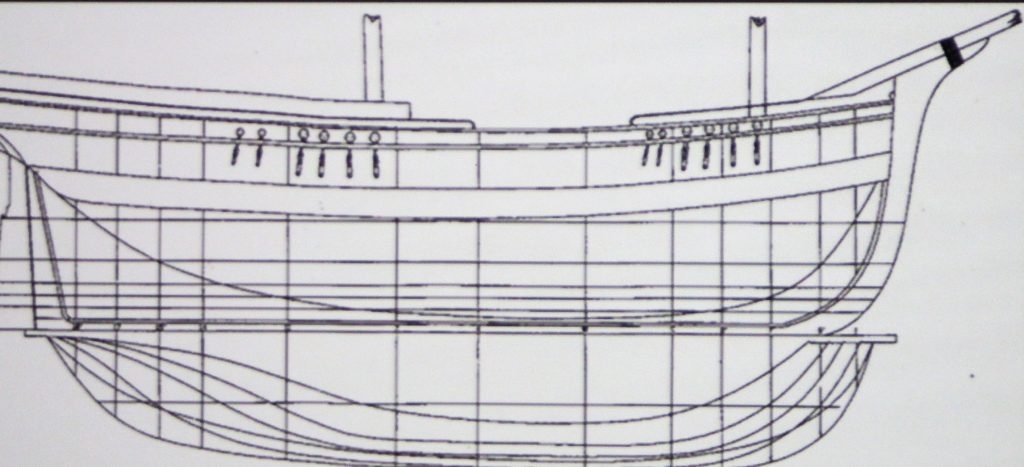

“Cornwallis brought from Wilmington NC 50-60 ships in a convoy. He took them all to Yorktown, where he set up a port to accommodate his ships and troops. Besides the warships, around 40-50 transports carried certain shipments. They might be for horses or troops or artillery or food.”

The ship he found carried coal. It was scuttled along with perhaps ten others to foul the coast so the French would not invade amphibiously. “In the 1980s the National Park Service issued a grant to build a steel envelope around the ship as a cofferdam. We chose a small ship, a two-masted frigate, well-preserved.” Of all the ships under the York, it may be the most intact.

“We found well-appointed artifacts because the captain owned the boat and wanted a nice place to live. Windows still had the glass in them. Colonial Williamsburg helped identify numerous important artifacts. Wonderful glass bottles had a beautiful glaze patina from years of preservation underwater.

“We discovered 10,000 rounds of musketballs, which is ironic. One reason the British surrendered was that they ran out of ammunition. I can imagine before they scuttled this ship that they started to remove the musketballs and found them too heavy to get off all at once.”

He added, “The grant included money to filter the water so you could see it from a pier that we built out to it from the Yorktown beach.”

Broadwater spent years traveling around England to trace the lineage of this one transport. He landed finally in Whitehaven near the Scottish coast, where he learned the captain was named Joseph Younghusband. “His mariner work had him transporting coal to Dublin, and he probably got caught up in the war to haul coal for the British.”

Younghusband died in 1782 in Charleston at the age of 51. “You can see his wife’s name Elizabeth on his gravestone. That explains the name of the ship at Yorktown. It’s definitely The Betsey.” He pointed to a post underwater. “This is five feet remaining of the mast.” Younghusband never thought his ship would wind up under the York.

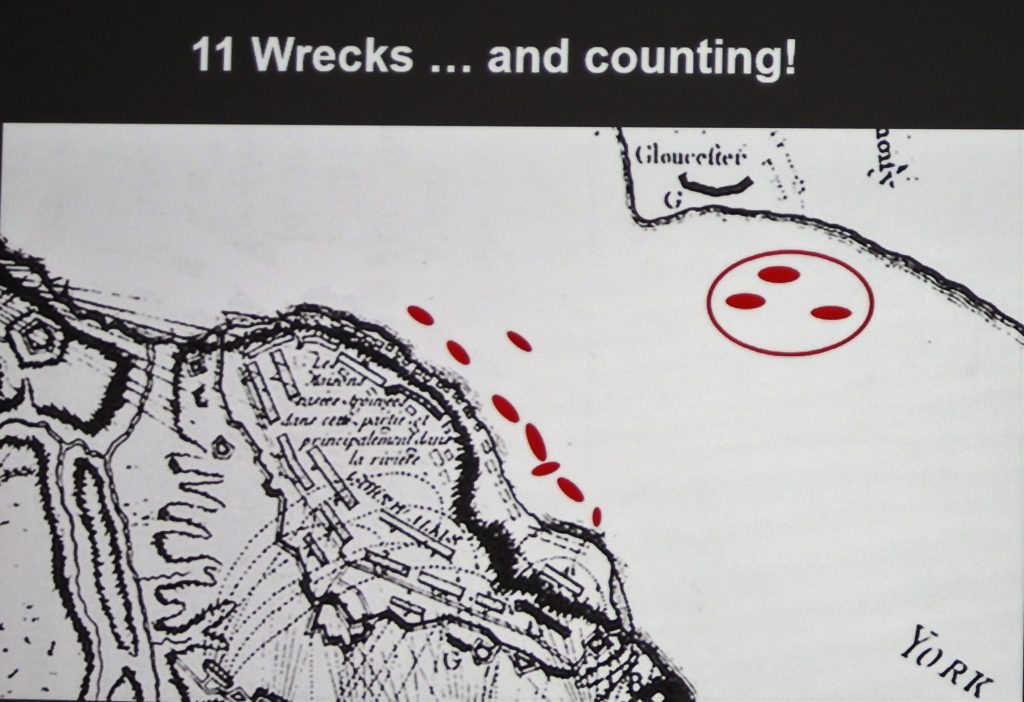

Last year Broadwater and his partners set out to identify more ships in the York. They moved to the other side, near VIMS, where Cornwallis’s flagship got blown up.

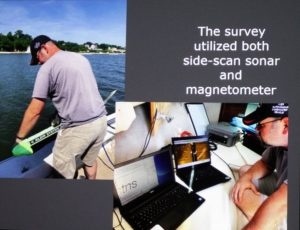

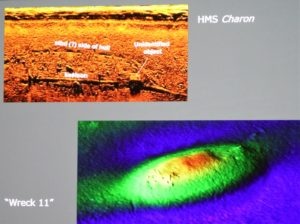

“The French fired red hot cannonballs just as the Siege started, so the British took the Charon and two smaller ships away from Yorktown and over to the other side. In recent the years, the science of archaeology has improved so we can use side-scanners and magnetometers.

“We found cannons on a new shipwreck discovery. It wasn’t a ship of the line but rather a transport. Many of these transports were armed to defend themselves in battle.”

Last summer The Washington Post showed up for a story about No. 11. “We took them out there and look what we found, a cannon!” That’s considered the Holy Grail among archaelogists, on land or sea. The Post article picked up the story with Diver Bill Waldrop in 23 feet of water when he bumped into something.

“What is this?” he thought. “I got on it, and I’m trying to move it. It ain’t moving… I started digging on the sides. How big is this thing?”

It felt round, like the barrel of a cannon. “I’m like, I’m not that lucky,” he said as he recounted the moment. “This is going to be a winch or something like that.”

The more he dug, the more excited he became. “This is iron, and this is big,” he thought. He knew the rear end of old cannons had a large knob called the cascabel, used to handle the gun.

As he probed, there it was. He thought, “This is a damn cannon.”

It was a diver’s dream.

He headed for the surface and started yelling, “I found a damn cannon!”

The suspected cannon, about seven feet long, is “almost certainly British,” Broadwater said. “It’s not big enough [to be from] a warship. It’s probably [from] one of the merchant vessels that was here. Almost all of them were armed, with anywhere from three-pounders to four- or six-pounders.”

At his library talk, Broadwater expanded briefly, “On Wreck No. 11 we have found at least seven cannons. We found charred wood as well, proving that it burned.” He did not elaborate with any photos of the cannons, perhaps holding back for greater exposure later. The green image of the ship’s outline was the only revelation. Regardless, it remains an important find among ships under the York.

“In 2020 we plan to spend more time down there. Oyster shells cover a lot of the wreck and they are very sharp. We go through a pair of rubber gloves in just one dive.” Almost as an aside, he mentioned, “We have t0 scrape through 6-12 feet of mud to get to some of these artifacts.” Not 6-12 inches but feet!

York County has posted a promo for an upcoming television series. Future episodes of the National Geographic series “Drain the Oceans” will feature details of the latest findings and presumably show exclusive video.

“Even though we’re excited by the finds, a colleague reminded me that we identified 11 but have 26 to go.” They have applied for grants and seek private donations as well.

State Funding Sank

Back in the 1980s, Broadwater was going strong and hit the jackpot with a big story in National Geographic. Then his state funding suddenly ended.

“This was when Gov. Wilder was cutting budgets, in 1989. He wanted to tell Virginians how dire things were, so he went on live TV to give the speech. My wife and I were sitting on the couch at home watching it when he opened by saying, ‘Some of my decisions to cut the budget are going to be easy. Can you believe that we have been funding an underwater archaeology project?’”

Broadwater paused, “You gotta laugh to keep from going crazy.”