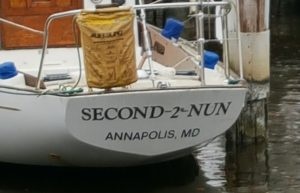

On an annual Christmas stopover before  St. Michaels, we walked around the port of Annapolis to check out boats and boat names as if we were Sailing Annapolis. The imagination runs wild.

St. Michaels, we walked around the port of Annapolis to check out boats and boat names as if we were Sailing Annapolis. The imagination runs wild.

Across from town, Eastport formed its own “island nation” and there is where many of these boats are berthed. They recently celebrated 150 years of freedom with detailed murals painted on the sides of otherwise drab buildings.

Across from town, Eastport formed its own “island nation” and there is where many of these boats are berthed. They recently celebrated 150 years of freedom with detailed murals painted on the sides of otherwise drab buildings.

A few years ago the Annapolis Yacht Club burned down. It has come back with a vengeance, occupying the original large building in Annapolis as well as two large buildings sprawling in Eastport.

Waiting List

I snuck in the back gate and saw a waiting list for slips that goes back ten years for specific slips. I asked a fellow passing by if that could possibly be true. He said, “Our sister marina in Florida has a waiting list of 20 years for certain slips.”

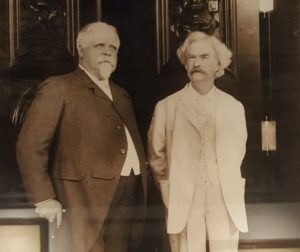

Sailing Annapolis is steeped in history, much of it associated with the US Naval Academy. Among the famous to visit town was Mark Twain in 1907, shown here with Gov. Warfield in his classic white suit.

Sailing Annapolis is steeped in history, much of it associated with the US Naval Academy. Among the famous to visit town was Mark Twain in 1907, shown here with Gov. Warfield in his classic white suit.

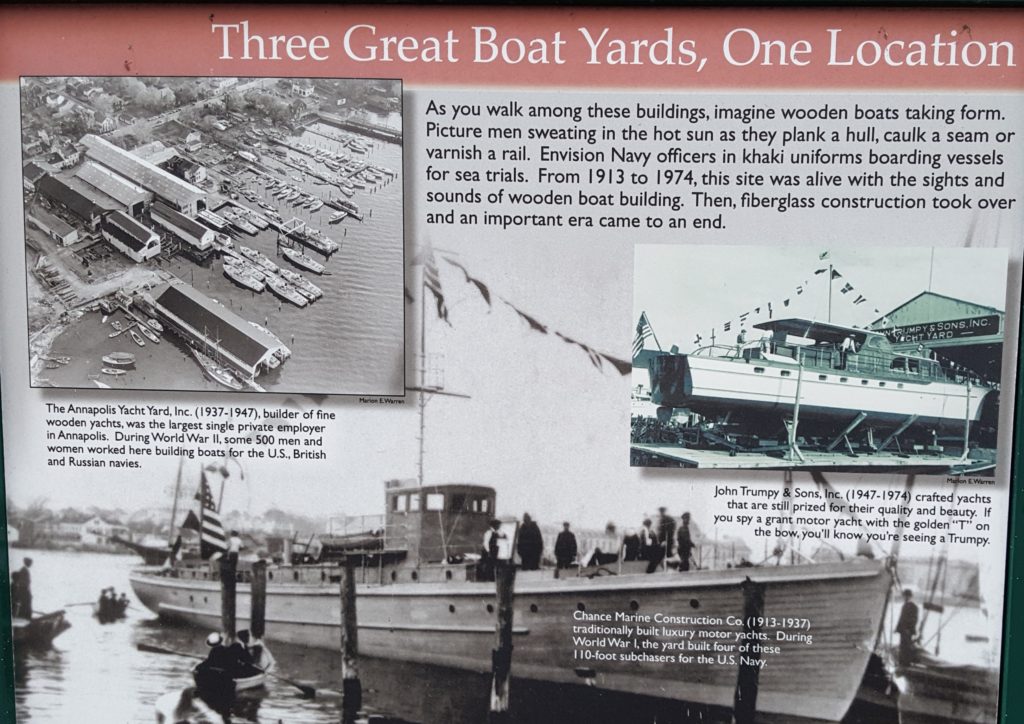

A classic photo of the downtown City Docks could have been taken in the 1800s but was actually 1955. This was just before fiberglass replaced wood as the structure of modern boats. “Three Great Boatyards” below describes the busy activity of wooden boat construction up until 1975. My favorite is Chance Marine Construction Co., which built luxury yachts 1913-1937. You have to possess a lot of confidence to name anything Chance, much less a shipyard.

A classic photo of the downtown City Docks could have been taken in the 1800s but was actually 1955. This was just before fiberglass replaced wood as the structure of modern boats. “Three Great Boatyards” below describes the busy activity of wooden boat construction up until 1975. My favorite is Chance Marine Construction Co., which built luxury yachts 1913-1937. You have to possess a lot of confidence to name anything Chance, much less a shipyard.

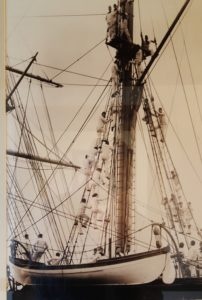

Another photo of sailing Annapolis is of a Navy seamanship drill, taken in 1893. Note how far up they’ve climbed the mast. (Sepia photos are from the lobby of the Annapolis Waterfront Hotel.)

St. Michaels

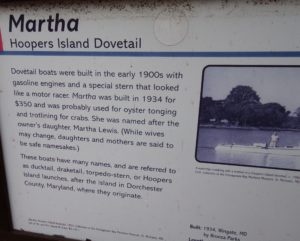

Across the Chesapeake Bay lies St. Michaels, made famous in the War of 1812 for allegedly scaring off the British by flying kerosene lamps high in the sky. The story is bogus but the myth is fun. The Chesapeake Maritime Museum has numerous classics on disply, including the Hoopers Island Dovetail named Martha. “She was named after the owner’s daughter, Martha Lewis. (While wives may change, daughters and mothers are said to be safe namesakes.)” Only could you find these while sailing Annapolis.

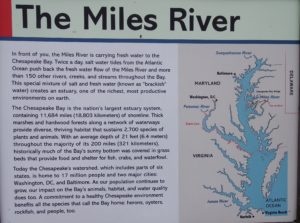

St. Michaels lies on the Miles River, one of 150 waterways off the Bay. Here is America’s largest estuary system, with 11,684 miles of shoreline — more than all three ocean coasts. Surprisingly the average depth is only 21 feet, which is why the Bay is so rough in a storm. The Chesapeake watershed spans six states and reaches as far north as Cooperstown NY.

St. Michaels lies on the Miles River, one of 150 waterways off the Bay. Here is America’s largest estuary system, with 11,684 miles of shoreline — more than all three ocean coasts. Surprisingly the average depth is only 21 feet, which is why the Bay is so rough in a storm. The Chesapeake watershed spans six states and reaches as far north as Cooperstown NY.

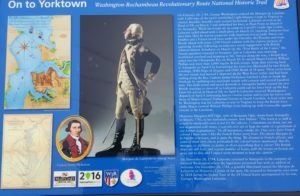

Finally we return to Annapolis to connect the dots to Virginia. A plaque near Eastport heralds the arrival of the Marquis de Lafayette. “On to Yorktown” describes how Gen. Washington ordered him to leave Annapolis from what is now Spa Creek to lead 1,200 men in a charge on Richmond. Eventually Lafayette would chase Lord Earl Cornwallis all the way to Yorktown, where the final battle effectively ended the Revolutionary War. He stopped short of sailing Annapolis.

Finally we return to Annapolis to connect the dots to Virginia. A plaque near Eastport heralds the arrival of the Marquis de Lafayette. “On to Yorktown” describes how Gen. Washington ordered him to leave Annapolis from what is now Spa Creek to lead 1,200 men in a charge on Richmond. Eventually Lafayette would chase Lord Earl Cornwallis all the way to Yorktown, where the final battle effectively ended the Revolutionary War. He stopped short of sailing Annapolis.

Guide beyond Sailing Annapolis

From the day the Museum of the American Revolution opened in Philadephia in 2017, guests have asked if there was a book available that captured the spirit of the core exhibition. This past July, the Museum released othe Official Guidebook, comprising American history in a nutshell. As with the Philadelphia exhibits, it’s divided into sections, two of which are printed here. They show that as late as 1775 America’s revolutionary future was not so obvious. Yorktown was still six years in the distance.

British America

In 1763, many British Americans were proud to be part of the most powerful empire in the history of the world. In that year, a peace treaty between Britain, France, and Spain ended the Seven Years’ War. This victory gave Britain an empire that stretched around the globe, including all the lands east of the Mississippi River.

Perhaps two million or more colonists inhabited this land. Most of these colonists celebrated Britain-and King George III-as the greatest protector of liberty in the world. They believed that the King would provide them with order, peace, religious freedom, and the right to representation.

In addition to the British colonists, there were another million or more people living on these lands. They included Native Americans, former French and Spanish colonists, and enslaved and free African Americans. Their relationship to the British crown, and to their colonial neighbors, was complicated.

In addition to the British colonists, there were another million or more people living on these lands. They included Native Americans, former French and Spanish colonists, and enslaved and free African Americans. Their relationship to the British crown, and to their colonial neighbors, was complicated.

Native Dilemma

Native Americans had to decide to fight or to accept that the British had claimed the land that had been their home for thousands of years. Some hoped the King would help them protect their lands from Colonial settlers. Others thought that war was the best strategy for safeguarding their homes.

About one in five Americans was enslaved, some born in America and others captured and carried across the Atlantic from Africa. Some enslaved African Americans whispered rumors that King George III might have sympathy for their cause.

But virtually no one expected large numbers of Britain’s colonists who had fought for the empire in the last war to have a problem with their king. The next decade proved that in politics, nothing is certain

Decade of Resistance

Britain’s 1763 victory in the Seven Years’ War brought turmoil rather than peace. Britain claimed millions of acres of French, Spanish, and Indian lands in North America – but this territory saddled the empire with massive political and economic challenges.

In 1763, some Native American nations rose up against British forces and forts in their homeland in Pontiac’s War. To ease tensions, King George closed Indian lands to new settlement, stationing troops in frontier forts to keep peace. Then the British Parliament imposed a tax-the Stamp Act of 1765 — to support these troops.

Tensions Grew

Parliament repealed the Stamp Act and replaced it with another set of taxes, but Americans opposed those too. Tensions grew, particularly in Boston, where the British Army sent regiments to protect customs officials in 1768. Violence exploded when a crowd attacked a British guard on March 5, 1770, culminating in an event the colonists called the Boston Massacre.

In 1773, the British government tried to boost the struggling East India Company with an exclusive right to import tea directly to America from London. But Americans interpreted the Tea Act as creating an unfair monopoly and as clever persuasion. On the night of December 16, 1773, colonists dressed as Indians boarded a tea ship in Boston Harbor, dumping the contents into the water.

Let’s Go Sailing Annapolis

Check rates and pick a day for a sailboat charter. See reviews on Trip Advisor.