UPDATE: Sept. 20, 2020: News Release by JRS Explorations

Survey of New Wreck Completed

During Sept. 13-18, 2020, JRS Explorations Inc. conducted an extensive shipwreck survey within the Yorktown Shipwrecks National Register District, thanks to the efforts of experienced researchers.

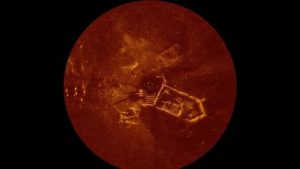

The goals were to survey and map “Wreck 11,” a recently discovered wreck in the York River near Gloucester Point. This wreck, which contains at least seven iron cannons, was discovered on a JRS expedition in 2019. The wreck proved to be the most difficult of the York River wrecks to study, due to several factors. These included near-zero visibility, strong tidal currents and a thick covering of oyster shell that impedes efforts to trace the edge of the hull to determine the size and shape of the wreck beneath.

The wreck was relocated using a side scan sonar, then PVC pipes were inserted around the perimeter of the wreck. This survey was another step in JRS Explorations’ long-range research plan for this group of internationally significant shipwrecks.

The 11 wrecks discovered since 1975 played an important role in the Siege of Yorktown in 1781, the last major battle of the American Revolution. The battle ended on Oct. 19 when Major General Charles Cornwallis surrendered the British forces under his command. A combined army consisting of American Continental Army troops commanded by General George Washington, and French units commanded by Comte de Rochambeau won the battle.

Half the Story

What many do not realize is that the battlefield in Yorktown only represents half the story. The other half remains on the bottom of the York River. As many as 40 or more British ships were sunk by enemy cannon fire or deliberately scuttled near shore by Cornwallis to prevent the French from landing troops on the beach behind the British position.

After nearly 239 years, JRS Explorations is making an effort to ensure that the history buried in the York River is protected. Dr. John Broadwater, JRS Explorations vice president and chief archaeologist, directed the York River survey. During the 1980s John directed the excavation of the British transport Betsy from within a cofferdam steel enclosure)in the York River, recovering more than 5,000 artifacts. Some of them are on exhibit today in the new American Revolution Museum at Yorktown.

Joshua Daniel, archaeologist and owner of Seafloor Solutions LLC, conducted the remote sensing survey of Wreck 11 and headed the dive team that placed PVC pipes around the perimeter of the hull. Bill Waldrop, owner of Waldrop Diving Services, provided the research vessel and the Watermen’s Museum in Yorktown once again provided logistics and support and served as expedition headquarters.

Wreck 11 is the Shipwright

Located near the wreck of the largest British warship, HMS Charon, Wreck 11 is believed to be one of the two transport vessels that collided with Charon and were set afire and sunk. The location and size of Wreck 11, along with the number and size of the cannons, suggest that it may be the transport Shipwright. More research will be necessary to verify this possibility.

JRS Explorations’ CEO Ryan Johnston stated, “JRS Explorations is grateful to the continued efforts of our research and dive team who make these investigations possible. We are accumulating valuable data that is helping shape our long-range research plan for these important shipwrecks.”

Daniel summed up the survey: “These shipwrecks represent a tangible part of one of the most significant events in the founding of the United States. It is a true privilege to be able to contribute to the knowledge of that moment in history through the study of these wrecks.”

Steve Ormsby, president of JRS Explorations and the Watermen’s Museum, said, “Surveys of the York River sshipwrecks help us rediscover key aspects of the decisive final battle of the American Revolution. Our principle goal is to gain new insights and share our information with the American public so we can all better understand the historic events that led to the founding of our great nation.”

JRS is currently evaluating possible next steps for investigating the archaeological potential of two shipwrecks on the Yorktown side of the river.

******

By Joanne Kimberlin

Staff writer, Virginian Pilot

YORKTOWN — John Broadwater sits on a boat in the York River, waiting for word from a diver below.

If this were a movie, it would be the perfect time for a flashback. The silver hair on Broadwater’s head would turn dark again, and viewers would be transported to 30 years ago — the last time he was here doing much the same thing. He’s back for a new look at his old shipwrecks.

Last week, for the first time in nearly three decades, archaeologists slipped into the murky York to assess what’s left of the Lost Fleet at Yorktown, a British convoy sent to its doom during the last major battle of the Revolutionary War.

For two centuries, the shipwrecks melted away — swallowed by time, silt and the elements. Alarm bells sounded in the 1970s after a diving magazine mentioned the wrecks, prompting an invasion of sport divers fetching artifacts for themselves.

Broadwater, wearing the official title of state underwater archaeologist back then, led a team mobilized to study, excavate and find ways to protect the remains.

In 1988, a 20-page spread in National Geographic detailed their accomplishments — more than 5,000 relics recovered for posterity from one wreck alone, a ship named Betsy.

But state budget cuts came shortly after, and Broadwater’s position was axed. Work stopped on the project, and relics went into storage — many of them uninspected, which led to a scramble just last year, when live hand grenades from The Betsey were discovered sitting on shelves at the Department of Historic Resources in Richmond. That was a new look at an old shipwreck.

After the cuts, Broadwater had to move on. He oversaw the salvaging of the Monitor, the famed Civil War ironclad that went down off North Carolina. Then he helped Jeff Bezos retrieve sunken rocket boosters from Apollo moon missions. Ultimately he worked with movie director James Cameron in the North Atlantic, descending more than two miles to the Titanic, eating his lunch in a submarine perched on the legendary liner’s grand staircase.

But the Yorktown shipwrecks kept calling to him. It was more than just the nagging of a job left unfinished. Last year, Broadwater and two partners — Ryan Johnston and Steve Ormsby — formed JRS Explorations, largely to return to this river.

“The three of us share a passion for this story,” he says.

Now, at 75 years old, Broadwater has come home. He’s working with volunteers — some from the old Betsey days. There’s no hope of getting rich by finding treasure. All relics will belong to the public, a pledge embedded in the company’s incorporation papers.

Now, at 75 years old, Broadwater has come home. He’s working with volunteers — some from the old Betsey days. There’s no hope of getting rich by finding treasure. All relics will belong to the public, a pledge embedded in the company’s incorporation papers.

Sitting on the boat this crisp, spring morning, Broadwater looks pretty happy. The locations of 10 wrecks are known but remote surveying done last spring hinted at some never-before-discovered targets, like the mound of rocks the diver is down there investigating right now. They might be ballast.

Today’s electronics — navigation systems, sonar, sensors — are way more precise than yesterday’s. A magnetometer detected the presence of metal around those rocks. Could be nails or iron from an old ship.

“It feels really good to be back,” Broadwater says, blue eyes shining.

Sandwiched between Yorktown and Gloucester Point, he’s in a natural spot to re-tell the story of what happened here 238 years ago.

“You just can’t make up fiction like that,” Broadwater says. “If anything had gone differently or happened one or two days later or earlier, well, the what-ifs are just endless.”

As he talks, the peaceful setting around the boat seems to fade away. The neat lawns lining the riverbanks. The kids playing with sand buckets on a beach. The whoosh of traffic over the nearby Coleman bridge.

As he talks, the peaceful setting around the boat seems to fade away. The neat lawns lining the riverbanks. The kids playing with sand buckets on a beach. The whoosh of traffic over the nearby Coleman bridge.

In a movie, it would be time for another flashback.

Six years into the Revolutionary War, the York River bristles with the masts of British ships. It’s the fall of 1781 and the village up on the bluffs is in ruins.

Sixteen thousand troops from the Continental Army and its French Allies are dug into dirt redoubts ringing the town, trading shots with 8,000 British troops trapped against the river.

The bombardment is relentless — cannon, howitzers, mortar — a slug-fest hammering day and night.

But the British commander, Lord Charles Cornwallis, isn’t giving up. He’s expecting reinforcements to sail into the river any day.

Instead, French 74-gun warships show up, having run off the British armada at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Cornwallis has 50 or so vessels of his own anchored in the river, but only a handful of small warships.

One of his best, the 44-gun Charon, has already gone down, set afire by red-hot shot aimed from shore.

Cornwallis tries every move in the play book.

He sets a few of his own ships afire and tries to drift them into the French warships. No luck.

He tries to slip away, loading his men into small boats to make for Gloucester, but a storm roars in and swamps the attempt.

Finally, he resorts to a tactic that’s been used by others: He sacrifices his own fleet.

Cornwallis sends a line of his ships toward the Yorktown beach until they run aground, forming a barrier he hopes will stop the French from landing troops.