For two years after the American victory at Yorktown in October of 1781, the Continental Army remained in the field. Peace with Great Britain was still uncertain. By March of 1783, Army officers and soldiers in Newburgh, New York, were growing impatient with Congress over back pay. Discord at headquarters was rampant.

An inflammatory address circulated at camp. It sugested that if Congress did not act, the army officers would challenge Congress’s authority. General Washington had to respond. In an address that brought tears to the eyes of those present, he delivered the famous ‘Newburgh Address.’ It quelled calls for mutiny and restored confidence in Congress.

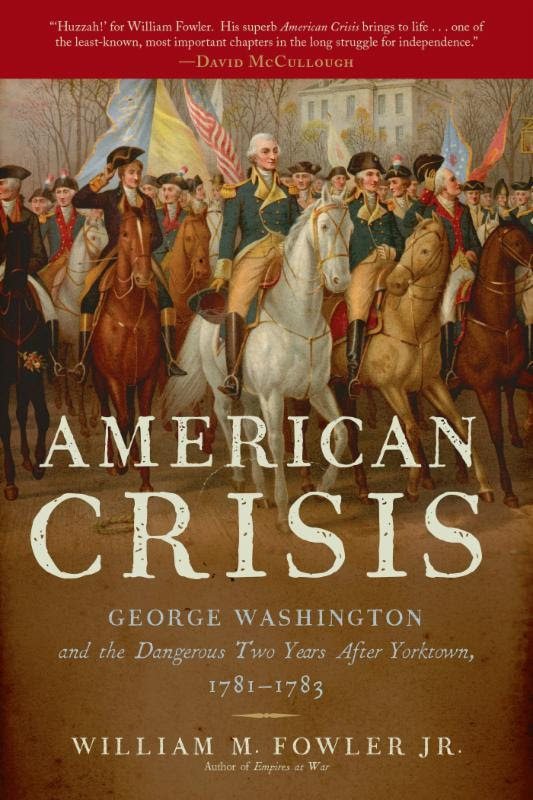

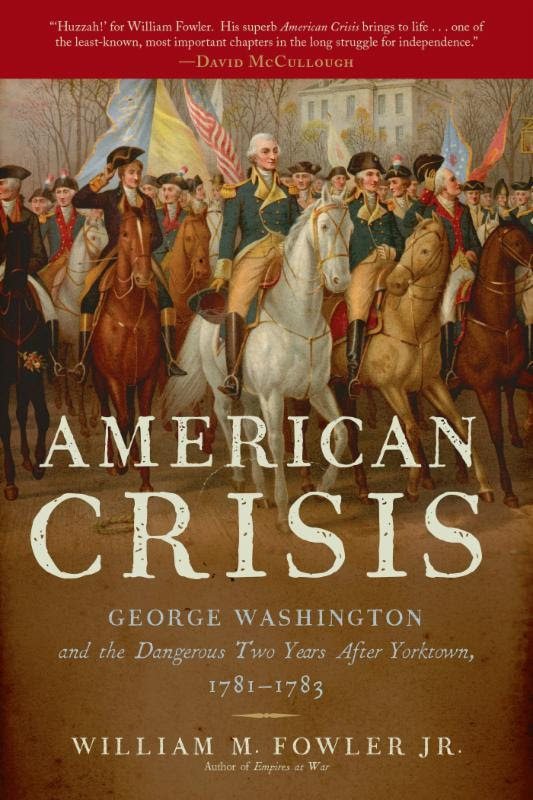

This excerpt is from American Crisis: George Washington and the Dangerous Two Years after Yorktown, 1781-1783, by historian William M. Fowler Jr.

-Condensed from the Museum of the American Revolution, Philadelphia

“On Saturday morning March 15 toward noon officers trudged up the hill to the public building. General Gates appeared from an anteroom and called the meeting to order. Within moments a tall figure dressed in blue stood in the doorway. Never before had the commander in chief come in person to address his officers. Even in the darkest and most perilous moments of the Revolution Washington had preferred back channels, third parties, or written communications.

“Washington began by apologizing for being there. Wrapping himself in humility and deference, he asked ‘the indulgence of his brother officers’ to grant him ‘liberty’ to read from his text. With that he took out a sheaf of papers and began.”

“His speech was delivered in the grand tradition of battle orations. The soldiers were demoralized, tired, and wanted to go home. Twice before during the war, both times in writing, Washington had reminded his officers of their duty and destiny by calling forth the image of King Henry’s ‘band of brothers.’”

“Ordinarily the general’s style was cool, deliberate, and restrained. This speech was personal. To those who would challenge his loyalty, he declared, ‘I have been a faithful friend to the army.’ ‘I was among the first who embarked in the cause of our common country.’ ‘I have been the constant companion and witness of your distresses.’ Washington entreated his men to permit him to make their case to Congress.

“Washington ended with a clarion call. By standing firm in defense of the country’s liberties, he told his officers, ‘you will, by the dignity of your conduct, afford occasion for posterity to say, when speaking of this glorious example you have exhibited to mankind-‘had this day been wanting, the world had never seen the last stage of perfection to which human nature is capable of attaining.'”

“The room was silent. The officers seemed unmoved. Washington feared that his message had failed. He looked out at his audience, paused, and took from his coat the letter he had recently received from Joseph Jones. He began to read portions of it to reassure the officers that Congress had their cause in mind. Major Shaw watched as the commander in chief paused, ‘took out his spectacles,’ the ones David Rittenhouse had sent only a few weeks before, and to which he was still becoming accustomed.

“’He begged the indulgence of his audience while he put them on, observing that he had grown gray in their service, and now found himself growing blind.’ It was an emotional moment, Shaw wrote, that ‘forced its way to the heart, and you might see sensibility moisten every eye.’ Washington ‘stood single and alone.’ ‘The whole assembly,’ according to Philip Schuyler, ‘were in tears.'”

|