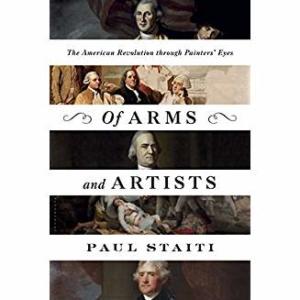

Next time you visit the U.S. Capitol Building, stand in the massive Rotunda and you will be surrounded by eight historical paintings. Revolutionary War veteran John Trumbull painted four of them, including the British surrender at Yorktown, (which figures big on the History Cruise of Let’s Go Sail.) In “Of Arms and Artists: The American Revolution through Painters’ Eyes,” Paul Staiti reconstructs the role of Trumbull and four other American artists in creating a lasting iconography of the American Revolution. Like Trumbull, Charles Willson Peale, John Singleton Copley, Benjamin West and Gilbert Stuart captured the war’s drama and helped to create an American mythology. The following excerpt discusses Trumbull’s effort.

–Courtesy Museum of the American Revolution, Philadelphia

“Feeling the spirit of 1776 and 1812, and eager to show the new national unity in a material way, congressmen voted for a resolution to hire John Trumbull to paint four huge Revolutionary pictures 12 feet high and 18 feet wide.

“President Madison himself discussed the choice of subjects with Trumbull. They agreed to balance two military with two civil subjects. Because the pictures needed to celebrate American success in the Revolution, gruesome battle scenes were ruled out. That eliminated the Death of General Warren and the Death of General Montgomery, Trumbull’s most dynamic paintings. Instead, they selected the Surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga and the Surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown as they highlighted the most civilized codes of warfare. The other two selections underscored civil achievement: the Declaration of Independence and General George Washington Resigning His Commission.

“President Madison himself discussed the choice of subjects with Trumbull. They agreed to balance two military with two civil subjects. Because the pictures needed to celebrate American success in the Revolution, gruesome battle scenes were ruled out. That eliminated the Death of General Warren and the Death of General Montgomery, Trumbull’s most dynamic paintings. Instead, they selected the Surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga and the Surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown as they highlighted the most civilized codes of warfare. The other two selections underscored civil achievement: the Declaration of Independence and General George Washington Resigning His Commission.

“Using the small version from the 1780s as a model, Trumbull undertook the large Declaration first in a new studio on Park Place, near New York’s City Hall. He finished it early in 1818 and then figured out ways to multiply his good fortune by taking the 216-square-foot painting on a triumphant tour across the Northeast before its delivery in Washington. Then he sold subscriptions to the $20 engraved version to be cut by a young print-maker.

“Citizens responded to his advertisement to view the Great National Painting, with admission set at 25 cents. The attendance figures were remarkable: 6,374 people came out to see it in New York. Gilbert Stuart and 6,395 others saw it in Boston’s Faneuil Hall. In Independence Hall, 5,189 braved the cold to see it in January 1819. And in the Baltimore Court House, 2,734 visitors saw it over the course of one week. Peale thought it ‘a fine picture on a difficult subject.’ It was difficult because the faces were from 42 years past, and viewers in 1818 had trouble recognizing them. While the 77-year-old Peale was in Baltimore he painted Trumbull’s portrait for his gallery of worthies.

“In all, a total of 20,701 journeyed out to see the Declaration of Independence, as if they were on a pilgrimage to a holy shrine. Like a secular crèche, it reenacted the nativity of the United States, and because it was visual it had extra appeal. Seeing it for the first time, visitors could believe that 1776 had come to life before their eyes. For many, Trumbull’s picture was etching history in the mind. ‘There is more history in the single canvass of Mr. Trumbull’s Declaration of Independence,’ wrote one Republican weekly, ‘than can be crowded into a folio of descriptive history.’

“Praise for the picture showered down on Trumbull like nothing he had previously experienced. A New York newspaper said that ‘no inhabitant of this country can view it without experiencing a deep sense of the hazards which the members of that illustrious assembly thus voluntarily assumed of the anxiety, the sufferings, and the triumphant success.’ The American Mercury went farther: ‘We gaze, then, with a degree of rapture on the exhibition…Every American ought to view this painting and take his wife and children to see it.’

“Trumbull delivered the painting to the Capitol on Feb. 16, 1819. The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis was delivered in November 1820. The Surrender of General Burgoyne arrived in March 1822. General George Washington Resigning His Commission came in 1824. They were all majestically installed with gilt-trimmed frames in the newly completed Capitol Rotunda in 1826, on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration.

“For all the praise, public criticisms predictably emerged, especially regarding the Declaration. Critics challenged whether the interior had been decorated inaccurately and why 12 of the original delegates to the Continental Congress were omitted. If George Clinton, Benjamin Rush and George Clymer had not signed the document, they should not have been in the picture when Caesar Rodney had been excluded. Some wondered, correctly, whether the painting depicted the actual signing. One critic identified as ‘Detector’ flatly stated that the picture ‘is certainly no representation of the Declaration of Independence.’ In fact, the errors, ‘with which it abounds, ought to exclude it from the walls of the Capitol.’

“Like other critics, this one felt that the proper goal of depicting the Revolution was ‘to hand to posterity correct resemblances of the men who pronounced our separation from Great Britain,’ not to indulge ‘the fancy of the painter.’ Unfortunately, in his eyes the ‘Great National Picture’ by Trumbull ‘sinks from the grade of a great historical painting into a sorry, motley, mongrel picture.’ As soon as it was installed in Washington, the critic continued, the picture will become a public ‘satire,’ a kind of buffoon rendition ‘of our own history.’

“The single overarching query was whether the Declaration of Independence was sufficiently accurate for viewers to feel confident putting their patriotic faith in it, or if it should it be viewed as a dramatization of 1776. While those were legitimate commentaries, the most penetrating observations about Trumbull’s project came from someone who knew what had really occurred: John Adams.”

Let’s Go Sail

Check rates and pick a day for a sailboat charter. See reviews on Trip Advisor. A little-known fact about the Surrender at Yorktown is that Trumbull’s brother was there. Since the painter’s custom was to put himself in grand works, he simply put his own face over that of his brother’s. You can tell it’s John Trumbull because he’s the only one looking the other way, and the only one whose horse is not visible.

American Revolution in Art American Revolution in Art American Revolution in Art American Revolution in Art American Revolution in Art