The history lecture that people enjoy at Let’s Go Sail derives from a slide show of 104 paintings of the Revolutionary War. It is called “The Art of War.” As a result, a research trip to Boston and Cape Cod this summer sought more details of the beginning of the Revolution.

Yorktown Ending

Now everyone knows that Yorktown ended the war, at least the fighting. Casualties at sea and on land surpassed a total of 1,000. By then, everyone was used to men fighting and dying for the war. However, no such ambivalence attended the first battle in Charlestown in June 1775, Bunker Hill.

Some 450 American patriots were killed and wounded, vs. 1,045 British. Technically it was a British victory, but it inspired the patriots to redouble their courage to resist the occupiers. Therefore, American casualties were a badge of courage that helped sustain the cause. And then six years later, their cause prevailed at Yorktown.

USS Constitution

Next, in downtown Boston lies the most iconic ship of the US Navy. Yet the USS Constitution dates to 1797 as one of the first six frigates built for the Navy. However, this was years after the Battle of the Capes, where the French fleet matched the British fleet and scared it back to New York.

Ultimately the woodwork is painted black with white trim, and the bright work shines with varnish. Remarkably, the ship’s wheel amid the foredeck is really two wheels so that two crewmen could wrestle with in a storm.

Loose Cannon

And the guns are so massive that they had to be lashed to the deck to avoid rolling around. So this is where the metaphor “loose cannon” came from. Not only that, they are as big as a small pickup truck and weigh twice as much. Finally at the Battle of the Capes, the warships on both sides carried 40, 60, 80 guns. Remarkably, the Ville de Paris was the largest warship in the world with 104 guns and 1100 men.

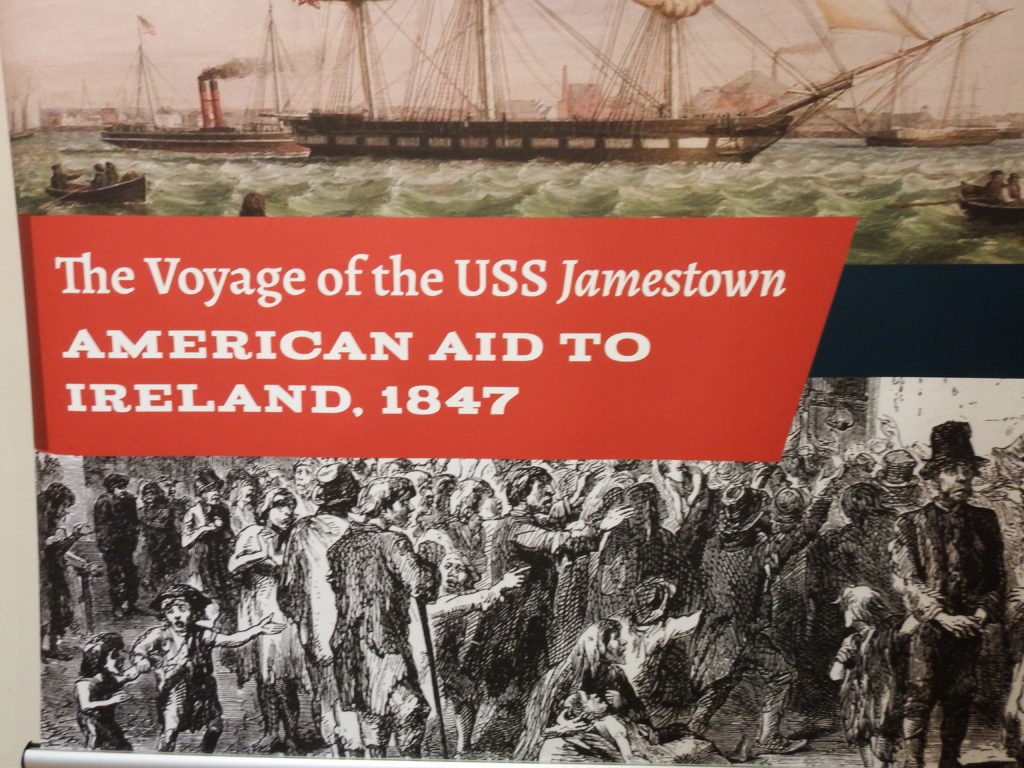

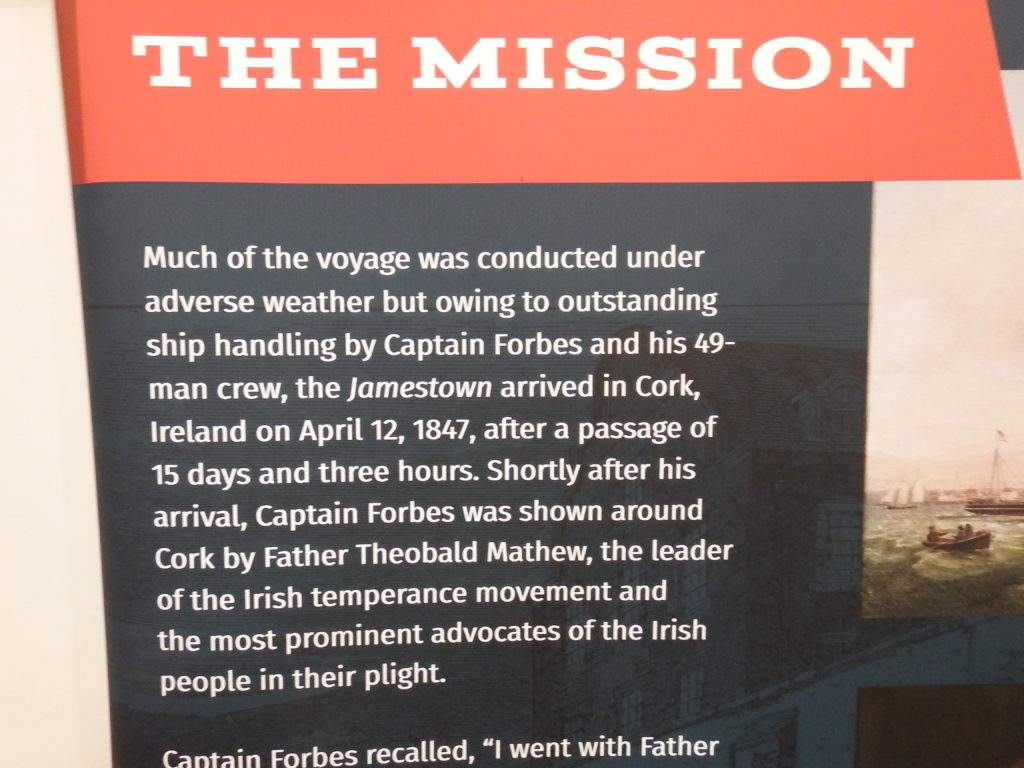

Today the museum for the Constitution includes a section on the voyage of the USS Jamestown, which in 1847 sailed to Ireland to rescue stranded citizens who were starving to death. Despite bad weather, the Jamestown made it to Ireland in just 15 days. While it would be nice to think the namesake was the original Jamestown in Virginia, it’s more likely Jamestown MA.

Yo Jamestown

Jamestown in Virginia gets short shrift by tour guides, even though the settlement predated Plymouth by 13 years. At Gloucester, they commemorate the founding in 1623 as “only three years after Plymouth.”

And they point to the huge stone formation near the coast as “the rest of Plymouth Rock,” attaching themselves adroitly to the Plymouth myth. Whenever I asked a guide about the 13-year discrepancy, they just stared at me. Much as we do when people from Florida cite St. Augustine as predating Jamestown by hundreds of years.

Gloucester

The Gloucester Maritime Museum pays homage to the seamen with dramatic paintings that haunt the imagination.

Gloucester is noted for their fishermen, some 10,000 of whom perished at sea. And a seaside memorial has 5,000 known names engraved, including Billy Tyne Jr. In 1991, he went down on the Andrea Gale in the book and movie, “The Perfect Storm.” As a result, respect is duly accorded annually with ceremonies near the statue of the woman with children peering out to sea in vain.

Boston

Then our tour included a trolley ride around Boston, where we saw the first statehouse downtown and the “new statehouse” of 1798 which still serves today. Vividly, the bight gold dome is visible for miles. As in Virginia, things that date back 200 years are still fairly new.

Next, the Gloucester Museum includes a wooden statue of the Madonna, but instead of the baby Jesus she is holding a fishing ship close to her breast to keep it safe from harm. Yet no such imagery attends Virginia art because it had much less interaction with the sea for fishing.

Moorings

Throughout New England one finds the picturesque scene of sailboats on moorings. But it’s a wonder they don’t have more marinas with fixed docks; the coastline must be too expensive and too exposed. Or in the case of this photo taken off Gloucester, the shoreline is too rugged to build any marinas.

I talked to a sailor who’s on the hook and he has grown fond of the thing. “They have a special mooring boat that takes people back and forth, so it’s hardly an inconvenience.” Except for getting on and off, and of course for securing electricity.

Edgartown

Next, at Edgartown, we saw the ferries to and from Chappaquiddick that Sen. Ted Kennedy famously missed the night he went off the wooden bridge on the island. Our guest lecturer on the matter once taught a graduate course and had the son of the local policeman who saw Ted that fateful night.

“I asked him after the course ended what do the police themselves think after all the years. Instead, he said the consensus was that Kennedy wasn’t even in the car when it went off the bridge. He saw the cop coming down the road in the distance and told Mary Jo, ‘I can’t be seen like this. I’ll get out, and you drive down there and come back and get me.” Tragically, she just drove too far.

A catboat with a unique sail purred along the inlet for all to see. By far, it was the most elegant of all the sailboats we saw.

Newport

At Newport RI we got to see The Breakers, perhaps the biggest Victorian house in America. Everything about it is over the top. One imagines what the Revolutionary War patriots would think of this today – excess in excess.

Out on the coast and several miles in the distance lies the first Coast Guard rescue station. Volunteers used to jump in rowboats and do their best to save crew members and passengers on fishing ships that went down.